And the unexpected benefits of listening to local talk radio.

One of the small things I noticed when I moved to California was how much people here love to talk about the highway. The wide-open roads of California are so awe-inspiring that they merit a definite article whenever they are referred to by locals. “Take the 101 south.” “Oh, you’ll need to hop on the 5 until you get to Stockton.” “Avoid the 1 on Thursday mornings, it’s a mess.” And Waze have mercy on your soul if a native Californian finds out you took an inefficient route to get somewhere, as they will drown you in a veritable numbers soup while attempting to educate you about the benefits of the 50 over the 5 on Saturday mornings.

I have even learned the difference between a highway and a freeway since moving here (all freeways are highways but not all highways are freeways, it’s a square-rectangle situation), knowledge that should help me immensely if I ever get a callback from ABC’s newest spin-off, Who Wants to be a Civil Engineer?

Maybe it was a consequence of growing up in Central New York, where for seven months of the year it’s snowing so hard your mother won’t let you outside to drive, but before moving out West I never gave much thought to our nation’s highways.

A lot of my friends in middle school played on a soccer team named after 481, a local section of interstate. I was always annoyed that there was no direct route on an interstate from Syracuse to New York City, forcing Central New York residents to drive either east to Albany then south to the city or south to Pennsylvania then east to the city. And twice a year my parents would pack me, my stuff, and an unlucky sibling or two into our minivan and drive nine hours west to South Bend, Indiana through some of the most boring stretches of the country imaginable. But that was, for a long time, the extent of the space occupied in my mind by highways.

Three years before I left CNY for California, the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) announced plans to either rebuild or replace the aging Interstate 81 (I-81) 1.4 mile viaduct that bisects the city of Syracuse. This announcement did not exactly rock my world. Having never owned a car, I best knew I-81 as the route I took to a Syracuse University basketball game with my friends. When I saw in the paper that the proposal to tear down the decrepit viaduct and replace it with a community grid was a popular option, I gave the matter no second thought. That is until, in the summer of 2018, when I overheard a segment on local talk radio where the host vehemently rallied against the grid option.

Never in my life had I heard someone so upset about an infrastructure change, and I roomed with a guy who was e consistently late to class in high school thanks to Governor Chris Christie’s illegal bridge closures. I started to read about the history of I-81 and Syracuse, trying to figure out why local conservatives were so mad about potentially removing a strip of interstate. Was there projected to be more traffic routed through the suburbs? Would the project run wildly over budget? The truth is much darker.

Some may recognize the name Bob Lonsberry from the aforementioned tweet, as he briefly went viral in November of 2019 when he declared the word “boomer” to be the “n-word of ageism”. He, and other CNY residents like him, were staunchly against tearing down I-81, instead calling desperately for the repair, rather than replacement, of the viaduct. Lonsberry and his ilk steeped their resistance to replacing a strip of highway in vague concerns about traffic flow. I spent an entire summer commuting north through the city via I-81 when I worked with my dad, and allow me to be the first to tell you Syracuse is not a large enough city to have serious traffic flow problems. But when a man who thinks “ok, boomer”, a meme used by young people to bottle up their anger at their decided lack of representation in the government, is equivalent to the n-word, a racial slur so heinous as to be referred to only by its first letter, started to criticize replacing I-81, I realized a deeper dive into the history of the interstate’s relationship with Syracuse was necessary.

Contrary to popular belief, many of the most segregated counties in America are located not in the Bible Belt, but rather the Northeast. Onondaga County, the home of the city of Syracuse, is by one measure the ninth most segregated county in America. This segregation is largely the modern consequences of two historical practices – redlining and environmental racism.

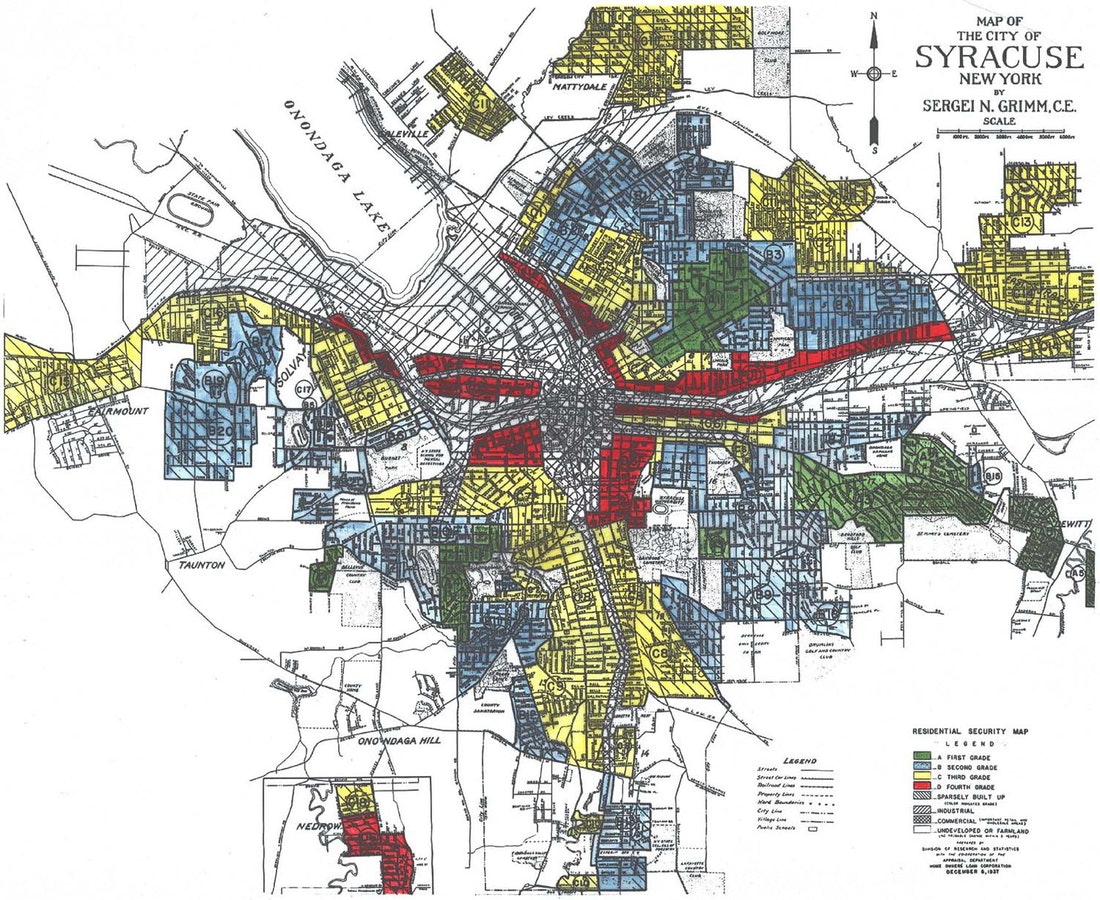

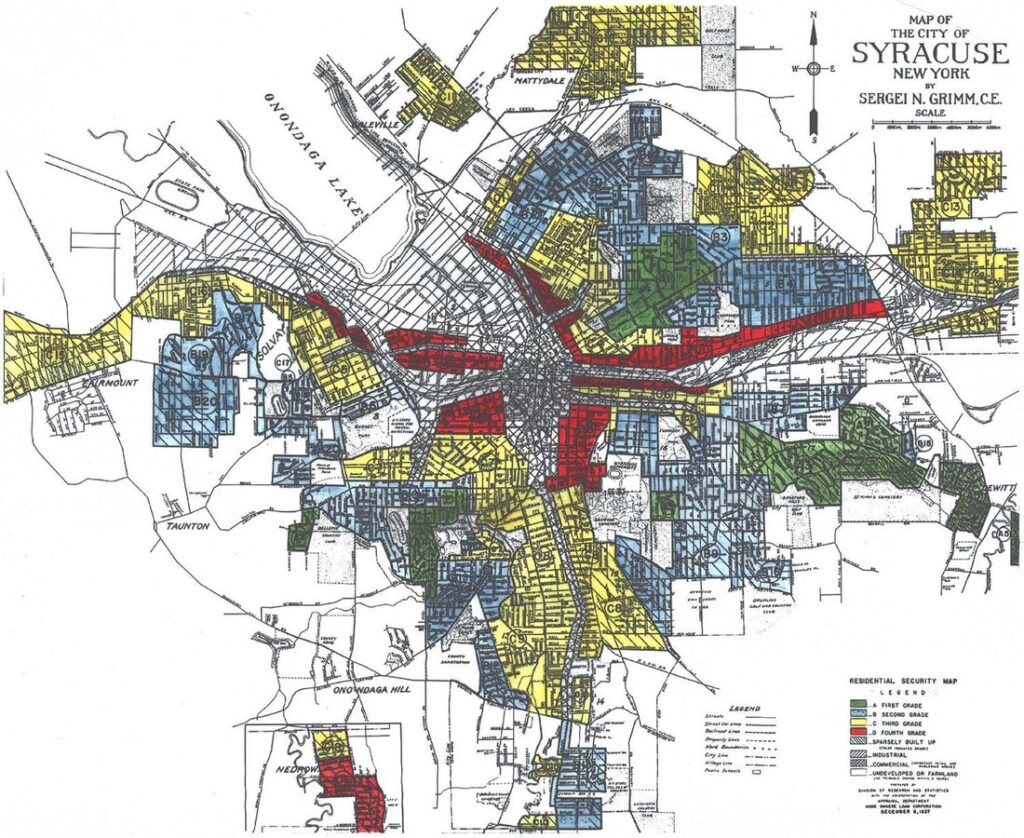

Redlining is the practice of denying mortgages to minority groups based on where they want to live. It has been historically used to keep neighborhoods segregated and to deprive minorities of home ownership. Under redlining, a majority Black neighborhood would be designated as “high-risk” by a bank. The bank would decline to offer mortgages outside these “high-risk” neighborhoods, and only offer loans at obscene rates for the “high-risk” areas, effectively depriving minorities of the possibility of home ownership. Syracuse’s 15th Ward was one of those historic Black neighborhoods. As the map above shows, it was quite literally redlined.

The 15th Ward developed naturally as a neighborhood grew around Syracuse’s first African Methodist church, which opened in 1911. The 15th Ward boomed as the Great Migration brought Black migrants to Syracuse after World War Two, many of whom were seeking jobs in Syracuse’s factories. Redlining was not outlawed until the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, so in Syracuse, as in cities across the nation, new minority residents were confined to the same few neighborhoods.

In 1956, the state of New York approved a $500 million ($13.1 billion in 2020 dollars) bond. The state and city intended to use this bond to construct I-81. There was only one problem – plans called for I-81 to pass directly through the city of Syracuse, which at this point was a rapidly growing community. Without consulting the people who lived there, the 15th Ward was selected by local officials as the neighborhood to be destroyed. The Atlantic put it best:

That this construction would destroy a close-knit black community, with a freeway running through the heart of town, essentially separating Syracuse in two, did not seem of much concern to local leaders. They wanted state and federal funding, and were willing to follow whatever plans were proposed to get it.

Alana Semuels, The Atlantic

Black people in Syracuse were forced out of their homes with little warning. An estimated 1,300 families were forced to move out of their homes that were located in I-81’s path. Today, the majority of Black residents in Syracuse reside in the city’s South Side, some of the most impoverished ZIP Codes in one of the most impoverished cities in the United States. Meanwhile, zoning laws still today keep wealthier suburbs inaccessible for lower-income families by mandating single-family homes and establishing minimum acreage for new construction. At the same time, the neighborhoods that currently abut the viaduct have some of the highest asthma rates in the nation. More than 90,000 cars pass through the strip of interstate daily, and the dust and exhaust create pollution at levels normally associated with factories and ports, creating a textbook example of environmental racism.

There is hope for Syracuse. After more than three years of protest, debate, and heated letters to the editor of The Post-Standard, a community grid proposal has won approval from the NYSDOT and been submitted to the Federal Highway Administration for a final review. At an estimated cost of around $2 billion, less than any of the other proposals, the viaduct will be torn down. The project is expected to create hundreds of local jobs. A new business loop will be created to service the city, merging I-81 with 490, another interstate in the region. Inside Syracuse, Almond Street will be expanded into a central boulevard. Regional leaders excited about the project share visions of pedestrians and cyclists traveling side-by-side with motorists, all making use of the new community grid to visit local businesses. Syracuse will no longer be, quite literally, split in half.

As I grow older and learn to question the “why” of everything around me, it saddens me to learn that even mundane structures such as a local highway can be symbolic representations of our nation’s discriminatory practices. Honestly, I never would have learned about the forced segregation in Syracuse, the city I grew up 15 minutes outside of, if it wasn’t for the rantings of a misguided local talk show host.

So thank you, Bob. Thank you for teaching me to question the history of every institutional factor that surrounds me. Thank you for teaching me about the racial weaponization of zoning laws. And most of all, thank you for being the most deserving recipient of an “Ok, boomer” I’ve ever seen.