I fear the city learned nothing from Destiny USA.

When I first moved to South Bend from Syracuse, I was struck by the parallels between the two cities. Both are small, Rust Belt-adjacent communities that receive an inordinate amount of snow whose economics are often dominated by the universities they host.

In 2020, I became aware of another similarity between the two metros – both will soon be home to Amazon warehouses.

At the start of my junior semester in South Bend, I was surprised to notice that some of my textbooks were now available with one-day shipping. Near-instant shipping in a city the size of South Bend? I was stunned. Having spent the summer interning in Chicago, I had only recently learned that one-day shipping existed in the first place. Now, I could order my textbooks (and LED lights, Halloween props, and other college student “necessities”) and receive them the next day without leaving campus. I was thrilled.

In the fall of 2019, Amazon opened an 84,200 square foot fulfillment warehouse in South Bend near the city’s small airport. The new facility supports between 100 and 200 jobs and pays a $15 per hour starting wage, more than double the Indiana minimum, which remains stuck at the federal floor of $7.25 per hour.

Initially, I thought this new warehouse must be great for South Bend. Like Syracuse, the city struggled with the loss of manufacturing throughout the second half of the 20th century. President Donald Trump’s trade war in 2018 hit the region hard, as the motor home factories in Elkhart (a large town outside South Bend) dealt with price increases for their raw materials and cut employee hours. A new employer offering employment similar to the manufacturing jobs that were lost in Elkhart seemed like a benefit to the South Bend community.

Then, I started noticing the hand-painted signs affixed to telephone poles around the city denouncing Amazon. Community activists, upset with the construction of the new facility, wanted Amazon out of South Bend. Despite the fact that neither the city nor county had given Amazon tax breaks, the warehouse was still unpopular with many in the area for a simple reason. The jobs it offers are of horrible quality.

The draconian worker conduct policies of Amazon warehouses are not new revelations. The digital shopping behemoth has been infamous for years for denying its workers bathroom breaks and expecting near-impossible levels of production. One woman in a New York City area warehouse said she was expected to sort 30 packages every minute, and if she failed to meet the goal, she would be reprimanded and eventually fired.

The coronavirus pandemic, which has been a boon to Amazon’s bottom line, further exposed the company’s abysmal treatment of its warehouse workers. At the start of the pandemic, as demand for online purchases from those isolating at home skyrocketed, Amazon fired warehouse worker Chris Smalls for organizing a walk-out over the unsafe working conditions at his warehouse.

By October of 2020, 19,816 Amazon employees had contracted coronavirus. This figure includes Whole Foods employees but does not include Amazon Flex drivers, who are considered to be independent contractors, and is the most recent figure I could find. The company has already been assessed two Occupational Health and Safety (OSHA) fines for violating COVID-19 safety protocols.

Also in October of 2020, a leaked internal memo from Amazon revealed the extensive nature of the company’s union busting efforts. While Amazon’s astroturfing efforts, particularly on Twitter, have been public knowledge for a few years, their anti-union practices take questionable digital media practices to an entirely new level.

The leaked memo revealed that, in addition to a department within human resources, Amazon maintains a Global Intelligence Unit entirely focused on monitoring pro-unionization sentiments. This unit, contained within the company’s Global Intelligence Program, employs proprietary software to track union-adjacent keywords across the Web, such as in Amazon employee Facebook groups and on seemingly unrelated corporate mailing lists.

The phrase “Global Intelligence Program” is so cliché that it would be unbelievable in a James Bond movie, let alone as an actual department of one of the world’s largest employers. Yet it exists. Amazon would rather spy on the entire Internet than allow its workers to unionize.

All of this background information brings me to Syracuse. In December, I wrote about the damage done to Central New York by the construction of Interstate 81. When I shared the post on /r/Syracuse, the top comment responded that the real problem facing the city isn’t its legacy of environmental racism, but rather the lack of jobs. The commenter heralded the forthcoming Amazon warehouse in Clay (a large suburb on the north side of the city, for all my non-Central New York readers) as a potential beacon of hope for the community.

While I staunchly disagree with the commenter’s dismissal of I-81’s negative impacts on Syracuse, they were correct that, like South Bend, most large companies long-ago abandoned Central New York. The massive new Amazon development in Clay, expected to open in time for the holiday season of 2021, will serve as a last-mile delivery hub for Central and Upstate New York, parts of New England, and the Ontario and Quebec provinces in Canada.

Central New Yorkers and local college students may be exited at the prospect of new jobs and one-day delivery. But when I started reading about the details of the Clay fulfillment center, I immediately noticed some familiar red flags.

For one, Onondaga County offered Amazon a $71 million tax break to build the warehouse in Central New York. Longtime Central New York residents may recognize that number; it is nearly identical to the estimated $70 million in tax breaks that were given to developer Robert Congel in 2007 for his Destiny USA project.

Currently the eighth-largest mall in the United States, Destiny USA is one of the most prominent employers in the area. The mega-mall is home to approximately 5,000 jobs.

It was also an unmitigated tax disaster for the city of Syracuse.

Prior to the Destiny USA expansion, the mall employed approximately 3,400 people. That means the local government subsidized 1,600 new jobs (most of which are minimum wage retail jobs) at a cost of $43,750 per job.

The tax cuts offered to Congel and his development companies also allowed him to double dip and claim the tax breaks he received as paid income taxes, so residents were essentially reimbursing Congel and Destiny USA for taxes he was not paying.

These cuts, along with the subsequent income tax reimbursement, kept millions and millions of dollars out of the coffers of the municipal and county governments, dollars which could have been spent improving Syracuse city schools, roadways, or public programs.

Yet somehow, slightly more than a decade later, the local government is once again offering another very wealthy man Jeff Bezos, nearly the exact same level of tax breaks to incentivize his company. Once again, the new facility will be one of the largest of its kind. The Clay fulfillment center will occupy an estimated 3.8 million square feet when it is finished, making it the second-largest warehouse in the world and only 500,000 square feet smaller than Boeing’s world-record holder in Washington. And, once again, millions of dollars in tax revenue will be missing for years from the city’s schools and snowplows and the county’s roads.

Amazon estimates that it will hire 1,000 workers to staff the Clay facility, which means the local government spent even more lavishly to bring these jobs to Central New York. Each new Amazon job set the government back $70,000 in lost taxes.

The warehouse jobs will pay $15 per hour to start, which will be the state’s minimum wage in a few years. That $15 hourly wage the company loves to advertise might be a selling point in lower cost of living states like Indiana, but Amazon never mentions that it offers the same starting rate everywhere in the country, regardless of the area’s cost of living. The Clay facility will also be one of the company’s most automated facilities yet, according to Amazon, so who knows how long those jobs will be around for?

Anecdotally, I happened to chat with an Uber driver who worked in the new South Bend Amazon warehouse. He told me that he worked twelve-hour days for in the South Bend Amazon facility, yet he still had to drive for Uber on his days off to make ends meet. I later learned that one reason behind his struggles was likely Amazon’s policy of withholding all employee benefits for the first year of employment.

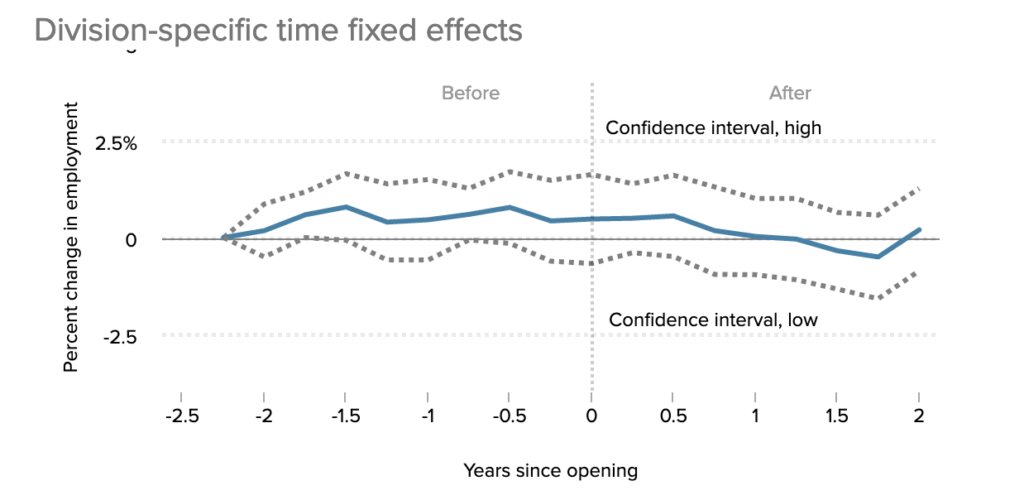

The kicker to all of this is that there is empirical evidence showing that new Amazon warehouses in small cities do not lead to noticeable gains in private-sector employment at the county level.

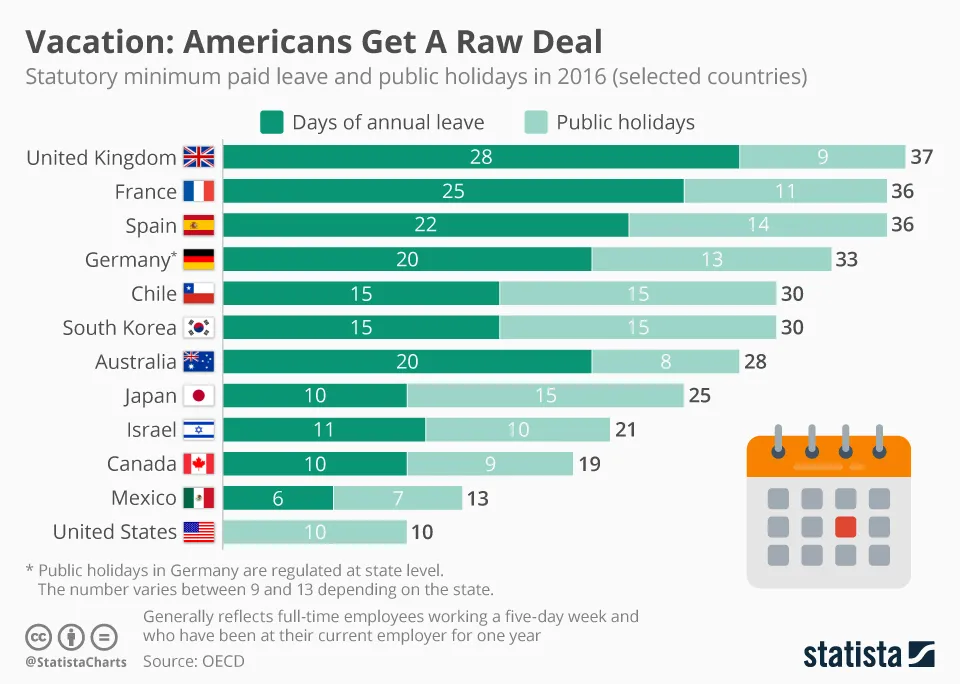

A report from the Economic Policy Institute, published in 2018, concluded that new Amazon warehouses lead to, at best, a 1.3 percent increase in private-sector employment in a county after two years. The same research from the think tank found that, for worst case scenarios, Amazon warehouses may actually lead to a 1.4 percent decrease in private-sector employment. The EPI recommended local governments invest would-be tax breaks in their infrastructure instead of giving the money away to one of the world’s largest companies. I have to agree.

It is baffling to me that Central New York’s leaders are making the same mistake with Amazon as they did with Destiny USA. While I genuinely hope the EPI and I are wrong and the Clay facility provides a much-needed jolt to Central New York’s economy, my expectations are low. After two years spent sharing South Bend with a shiny new Amazon building, I hardly noticed any changes to the local economy.

Furthermore, Amazon is clearly committed to automation. If the company invents a robot that can pick items off its shelves more efficiently than people, it will without a doubt replace its warehouse pickers with machines. Amazon will also do anything in its power, including full-scale, conspiracy-inducing spying, to prevent those same workers from unionizing to defend their rights and secure their jobs.

And, specific to Syracuse, the local government has made this mistake once before with Congel and Destiny USA. Strung along by a wealthy businessman who over-promised and under-delivered, the local tax base is still feeling the effects of the first $70 million it sacrificed for some jobs. Let’s hope the second $70 million boondoggle turns out better for Central New York. Syracuse needs all the help it can get.